Home » My Articles » The Dove Tail

The Dove Tail

The court rolls of the manor of Dulwich are an invaluable source of information, particularly for tracing family relationships over several generations or even centuries, and in no case is this more true than in that of the Dove family, who were involved in a dispute concerning Dulwich property which occupies a large proportion of the rolls for the first half of the sixteenth century. Following this interesting case-history is complicated by the fact that many of the participants shared the same name, that of John Dove. Even more confusingly, one of these John Doves had three sons, two of whom were also called John Dove!

The story begins in the 1420's with the arrival in Dulwich (probably from Cheshire) of one John Bruton or Breweton, who within a few years had established himself as reeve of the manor. As the steward of the manor was the lord's representative at the manor court, so the reeve represented the villagers at the lord's council. However, he was also a sort of land agent for the lord, paid on commission. He was personally liable if the targets for agricultural production weren't met, but stood to make a good living if the quotas were exceeded.

John Bruton evidently made a very good living. Over a period of nearly fifty years he built up his land-holdings in Dulwich, by judicious purchases, to over one hundred acres, far and away the largest holding by a single individual. Bear in mind that the total area under plough or pasture at this time wasn't much more than five hundred acres, and you will appreciate what an important figure he was. Thirteen of his acres (in Perifield, the site of William Penn School [now, in 2024, The Charter School]), were freehold, but the remainder were copyhold. This meant that they were held according to the custom of the manor, in theory at the will of the lord but in practice in perpetuity, in return for a nominal rent (normally a few pence a year) and an obligation to work for a number of days every year on the lord's land.

In 1472 John Bruton's copyhold property in Dulwich consisted of a messuage and 6 acres (formerly Robert Gonuld's), 17 acres called Morkynes, 12 acres in Northcroftes, 14½ acres (formerly William Westone's), 2 acres in le Apse, 3 acres on the north side of Brownings, a tenement and 30 acres (formerly Agnes Dene's), 2 acres in Middlefield and at Twaycrochyn, 2 other acres in Middlefield (formerly Richard Depeham's), 2 acres in Denesmede (formerly Richard Wythyr's) and 3 acres in Brownings (formerly John Lilborne's). The court rolls for that year record John Bruton's surrender of all this property to the use of himself and his wife Joan for life, with 'remainder' to John Dove "and the customary heirs of his body". The relationship between them seems to be that John Dove was the son of John Bruton's daughter Joan, whose husband may have been the Henry Dove who later fought and died with King Richard III at the battle of Bosworth Field, but the position is not entirely clear.

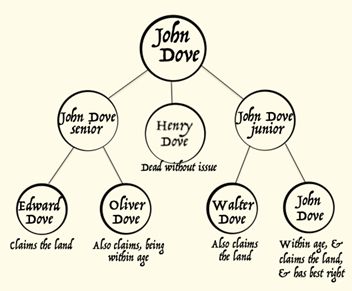

What is known is that in 1507 John Dove attempted a resettlement of his property, in order to make provision for all his family. Part of the land was to be held in trust for his wife Margaret for life, and on her death was to go to his eldest son John "and the heirs of his body". Another part was given to his second son Henry and the heirs of his body, with 'remainder' to the same son John likewise. The rest of the property was left to his youngest son John and the heirs of his body, with similar remainders over. Incidentally, to avoid getting hopelessly confused, we shall henceforth refer to the father as the first John Dove, to the eldest son as John Dove senior, and to the youngest as John Dove junior, as they were referred to in the subsequent litigation.

Before we proceed with the story, some explanation of the legal principles involved is unavoidable if we are to make any sense of what happened later. Consider the phrase 'the customary heirs of his body', used by John Bruton in the 1472 settlement. Until 1540, when the law was altered, land could not be disposed of by will or other testamentary gift. A man's heir was identified by applying legal rules of kinship, not by taking the deceased's wishes into account. Primogeniture was the basic rule, in other words where there were sons the eldest of them inherited. Where there were no sons, or their issue, more complex rules applied, but provided the claimant was able to satisfy the rules of evidence about proving kinship, there was always an heir. The rule of primogeniture was the common law of the realm, but could be displaced by a contrary local custom, if of accepted antiquity. This is of direct importance in our case, because in some manors, of which Dulwich was one, there was a customary law known as 'borough english', whereby on the death of a copyholder, strange as it may seem, his youngest son, not his eldest, was the heir. The only way around these rules of inheritance, whether common law or customary, was to create settlements of one's property during one's lifetime, dealing with present and future interests in the land, as John Bruton had done in 1472, and the first John Dove had attempted to do in 1507. Having said that, it is more than likely that the 1507 settlement as entered in the court rolls constituted the provisions of the first John Dove's last will. The ban on dealing with property by will was often circumvented by a shameless legal fiction, whereby two villagers came to the court and swore that, immediately before his death, the deceased had surrendered his property to them on certain trusts (i.e. those declared by the will). The actual court roll for 1507 hasn't survived, so we can only guess that this is what happened.

If a man made a settlement giving property 'to A and his heirs', he was parting with the largest interest which could exist in land. Because there was a virtually inexhaustible supply of potential heirs, the gift was effectively in perpetuity. Such an interest was (and still is) known as a 'fee simple'. What if the same man wanted to limit potential heirs to A's direct lineal descendants? He could do so by making the gift 'to A and the heirs of his body'. This created an interest known as a 'fee tail', the word 'tail' deriving from Latin and indicating that the fee simple had been 'cut-down'. From this followed an important consequence, which was again crucial to the Dove dispute: if land was given in fee simple 'to A and his heirs', A was free to sell or give away the property, but if the gift was in fee tail 'to A and the heirs of his body', no alienation of the property by A, the 'tenant in tail', was permitted (although there was a legal device used to circumvent this, which we need not go into), since the effect would be to disinherit A's issue, unless the issue who was the 'remainderman' (i.e. the person who would inherit on the death of the 'tenant in tail') consented to the alienation.

This was the position under common law, the law of the realm, but was there a case for claiming that these principles didn't apply to copyhold property? Yes, there was. It could be argued that, if a fee tail was recognised at all by customary law, the 'tenant in tail' was entitled to alienate at any time after issue were born to him. If this were so, then the customary fee tail created by John Bruton's settlement of 1472 would have been frustrated by the first John Dove's 1507 resettlement. The law was somewhat uncertain on this point, and it could be said that the Dove dispute was something of a test case.

The first John Dove probably died in 1507. John Dove senior died in 1521, his brother Henry followed without issue c.1525, and his other brother John Dove junior died in 1533. Margaret Dove, the first John Dove's widow, lived on until 1535, and the ending of her 'life interest' was the signal for battle to commence between her grandsons. When legal proceedings began in January 1536, John Dove senior's sons Edward and Oliver both claimed the land, as did John Dove junior's sons Walter and John. As Edward (aged 22) was the only one to have attained his majority (Oliver being aged about 16, Walter 13, and John about 4), no doubt the real conflict was between their respective guardians.

The litigation dragged on for two years, during which both sides must have incurred considerable legal expense (including a reference of the matter to the Court of Requests, and obtaining Counsel's opinion from Sir William Paulet, one of the most eminent lawyers of the day), until at the end of 1537 the case was resolved in favour of John Dove, the youngest son of John Dove's youngest son John Dove, if you follow. He was therefore admitted not only to the lands which his father John Dove junior had been given by the resettlement of 1507, and which had never really been in dispute, but also to the property which the first John Dove had tried to settle on John Dove senior and Henry Dove, instead of John Dove junior, by that same settlement. Thus it was held that the 1507 resettlement was invalid, as it contravened John Bruton's original settlement of 1472.

Incidentally, Oliver Dove died without issue not many years later, and was succeeded to the small amount of copyhold property which he held in his own right by his brother [not included in the above pedigree], the second youngest son of John Dove senior. His name, you will not be surprised to learn, was John Dove!

Patrick Darby

[First published in July 1982 Dulwich Society Newsletter No. 57. Amended and re-formatted 9 July 2024. Dove pedigree (adapted from Sir William Paulet’s Opinion) added 12 August 2024.]